Many people may already recognise Kakadu Plum as a remarkable Australian fruit, famed for its astonishingly high vitamin C concentration. However, this incredible super-fruit offers much more than just an impressive vitamin profile. Hailing from the heart of the Australian Outback, the Kakadu Plum (Terminalia ferdinandiana) has been revered by Indigenous communities for centuries not just for its nutritional benefits, but also for its rich history and cultural significance. What sets Kakadu Plum apart is its extraordinary potency. In fact, it boasts the highest recorded level of vitamin C found in any fruit, up to 100 times more than that of an orange! This powerful antioxidant is essential for maintaining a robust immune system, promoting skin health, and facilitating the body’s ability to absorb iron. This makes Kakadu Plum not only a powerful ally in warding off common maladies but also a vital player in maintaining overall wellness.

But the benefits of Kakadu Plum extend well beyond vitamin C. This unique fruit is also packed with a variety of other essential nutrients, including vitamin E, potassium, and fibre, among others. These components collectively enhance its reputation as a super-food, contributing to numerous health benefits ranging from improved digestion to better cardiovascular health. Moreover, Kakadu Plum is rich in polyphenols and other antioxidants that combat oxidative stress, helping to safeguard the body against the harmful effects of free radicals. Culinary enthusiasts are beginning to embrace Kakadu Plum not just for its health benefits, but also for its delightful flavour profile. The fruit has a tart, tangy taste that can add a refreshing twist to a variety of dishes. Health-conscious people can enjoy it in smoothies, as a tangy ingredient in salad dressings, or even as a zesty sauce for meats and fish. Its versatility makes it an exciting addition to both sweet and savoury recipes.

Kakadu Plum Powder May Help Protect Damaged Liver Cells

For those who enjoy indulging in their favourite alcoholic beverages, there’s promising news on the horizon: Ancient Purity Kakadu Plum Powder may offer some protective benefits for liver cells against the harmful effects of alcohol consumption. This powerfully nutrient-rich superfood, derived from the Kakadu plum, a fruit native to Australia, boasts remarkable antioxidant properties that can assist in combatting oxidative stress and inflammation within the liver. While this discovery may certainly pique the interest of social drinkers and connoisseurs alike, it’s important to emphasise that moderation remains paramount. The most effective way to safeguard your liver and maintain its health is to limit alcohol intake and adopt a balanced lifestyle. Incorporating Kakadu Plum Powder into your diet could serve as a supportive strategy alongside responsible drinking habits, promoting overall liver health. With its high concentrations of vitamin C and other vital nutrients, this super-food may not only enhance your body’s defences but also provide a delicious way to fortify your nutritional intake. So, while sipping your favourite drink, consider integrating this powerful powder into your diet and take a step towards better liver health.

Drinking a small amount of alcohol can help speed up your metabolism and lower the chances of heart problems. However, drinking a lot over a long time can lead to hangovers and serious health issues like liver disease, including hepatitis and cirrhosis, as well as muscle pain and other concerns. Studies have shown that heavy drinking is a significant risk factor for gastric cancer, which was the second most common cause of illness and the third leading cause of death in South Korea in 2014. One of the ways that alcohol harms the liver is through a process called oxidative stress, which is triggered by substances known as reactive oxygen species (ROS). This type of stress has been studied a lot.

When someone drinks alcohol, their liver works hard to break it down. The liver has many enzymes that help with this process, the most important being alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) and aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH). First, ADH changes alcohol (ethanol) into acetaldehyde, which is then converted into acetate by ALDH. However, drinking alcohol over time increases ROS production, which can hurt liver cells and even cause cell death. Additionally, excessive drinking boosts another enzyme called cytochrome P450 2E1, which also creates acetaldehyde and ROS. High levels of acetaldehyde and ROS can lead to unpleasant symptoms like nausea, sweating, and a fast heartbeat. It’s crucial to remove excess alcohol and acetaldehyde from the body to avoid damaging the liver.

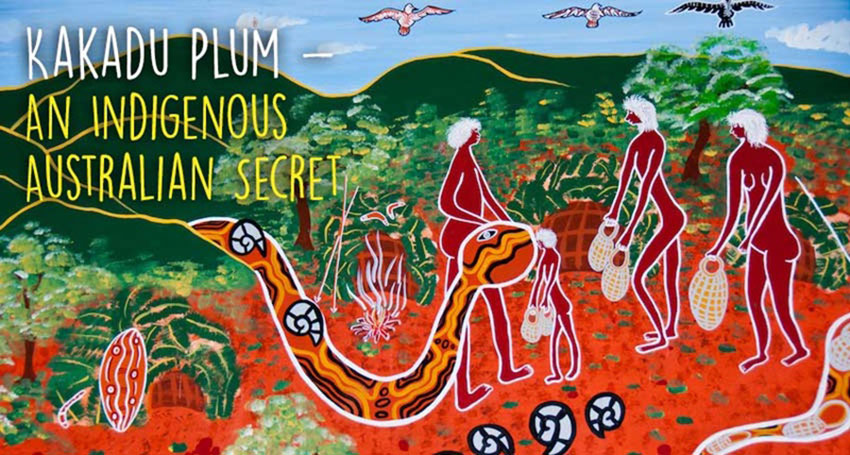

For thousands of years, many cultures have turned to herbal remedies to treat problems related to alcohol use. One such remedy is the Kakadu Plum. This fruit, primarily found in the Northern Territory and Western Australia, is often viewed more as a medicine than just food. In Western Australia, it goes by names like bush plum and billygoat plum. In the Northern Territory, Aboriginal people harvest this fruit for both commercial use and to support their way of life. Traditionally, the Kakadu Plum has been consumed as a refreshing drink, especially during hunting trips, as a source of energy.

The Kakadu plum is rich in vitamin C and has many beneficial plant compounds, like flavonoids and phenolic acids, which may have antioxidant properties. These compounds have potential health benefits, including fighting cancer, reducing inflammation, and combating bacteria. Research has shown that the vitamin C in Kakadu Plum can protect against the chronic toxicity caused by acetaldehyde from heavy alcohol consumption. Unfortunately, alcoholics often have lower levels of vitamin C in their bodies. However, it hasn’t been clearly established how Kakadu Plum helps with alcohol metabolism.

In this article, we aimed to create a laboratory model to explore how the Kakadu Plum from two regions of Australia, the Northern Territory and Western Australia, protects liver cells (HepG2 cells) from the harm caused by alcohol. We also looked at how the fruit affects two key enzymes involved in breaking down alcohol (ADH and ALDH) and investigated its potential antioxidant effects against alcohol-induced damage in these liver cells. Kakadu Plum fruit is rich in important compounds like ellagic acid and vitamin C, which are both known for their antioxidant properties. We measured the amounts of vitamin C, ellagic acid, phenolic acid, and flavonoids using a method called HPLC. Our findings indicate that the amount of ellagic acid in our fruit samples ranges from 0.01 to 0.36 milligrams per gram of dry weight (mg/g DW). In contrast, gallic acid amounts ranged from 0.13 to 5.10 mg/g DW. Recent studies also found high levels of ellagic acid and vitamin C in Kakadu Plum.

According to earlier research, Kakadu Plum has 75 times more vitamin C than oranges. Vitamin C is vital for humans; however, it can break down easily when exposed to high heat, water, or air. In our study, we used drying and reflux methods to extract the vitamin C, and we found that the plum from the Northern Territory (NT) had more vitamin C than the one from Western Australia (WA). Specifically, we measured 88.66 mg/g DW of vitamin C from the NT fruit and 52.83 mg/g DW from the WA fruit. Studies have shown that Kakadu Plum contains significantly more vitamin C than many other fruits, having 900 times more than blueberries, for instance. It is also reported to have a greater vitamin C content than traditional sources like lemons and oranges.

While lemons and oranges are often considered excellent sources of vitamin C, our results showed that Kakadu Plum has a higher concentration, even if extracted at higher temperatures, which usually degrade vitamin C. Remarkably, the vitamin C content in Kakadu Plum remained stable despite these conditions. Reports indicate that it has around 7000 mg of vitamin C per 100 grams of dry weight, which is 100 times more than what you would find in lemons and oranges. Furthermore, when compared with other fruits, our results confirmed that Kakadu Plum has a much higher level of vitamin C. To better understand its health benefits, we also looked at its isoflavones profile. According to our findings, *Daidzin was unique to Kakadu Plum and pomegranate, while it was not found or only appeared in very small amounts in other samples.

* Daidzin is a compound that belongs to a class of natural products known as isoflavones. It is primarily found in soybeans and is recognised for its potential health benefits, including antioxidant properties and possible effects on hormonal balance. Daidzin is particularly notable for its role as a phytoestrogen, which means it can mimic the action of oestrogen in the body. Research has examined Daidzin for its effects on various health conditions, including its potential in managing conditions related to menopause, osteoporosis, and certain types of cancer. However, as with many compounds, the results can vary, and further research is often needed to fully understand its effects and benefits.

Phenolic & Flavonoid Contents

Phenolics and flavonoids are important substances found in plants that help protect their cells from damage caused by oxidation and stress from the environment. To measure the total amounts of these compounds in different fruit extracts, including Kakadu Plum- Northern Territory and Kakadu Plum-Western Australia, researchers used two methods called the Folin–Ciocalteu and aluminum chloride colorimetric tests. The results showed a wide range of phenolic and flavonoid content.

Specifically, the total phenolic content ranged from 16.66 ± 1.32 to 147.2 ± 0.70 mg/g, reported in terms of gallic acid equivalents (GAE), while the total flavonoid content varied from 0.32 ± 0.02 to 1.30 ± 0.01 mg/g, measured as quercetin equivalents (QE). Previous research has found that the phenolic compounds Kakadu Plum are significantly more abundant than those in blueberries. In this study, Kakadu Plum consistently showed higher levels of both phenolics and flavonoids compared to the other fruits tested, based on the standards of gallic acid and quercetin.

Notably, Kakadu Plum-NT had much higher totals of phenolics and flavonoids than Kakadu Plum-WA. Following Kakadu Plum, pomegranates, oranges, lemons, blackberries, and raspberries had the next highest levels. This clearly indicates that Kakadu Plum is among the richest sources of phenolics and flavonoids when it comes to edible fruits.

Ethanol-Induced Cytotoxicity in HepG2 Cells & the Protective Potential of Kakadu Plum Powder

To investigate the protective capabilities of Kakadu Plum against ethanol-induced cellular damage, we first established the optimal ethanol concentration that triggers significant cell death in the hepatocellular carcinoma cell line (HepG2). HepG2 cells, widely recognised as a robust in vitro model for studying oxidative stress and toxicity, were exposed to varying ethanol concentrations ranging from 0.25% to 8% for 24 hours. Following exposure, cell viability was quantitatively assessed using the MTT assay, which measures metabolic activity as an indicator of cell survival.

Our results demonstrated a clear, dose-dependent decline in HepG2 cell viability correlating with increasing ethanol concentrations. Notably, at 4% ethanol, approximately 50% of the cells exhibited inhibited growth compared to untreated controls, establishing this concentration as a critical threshold for significant cytotoxicity. This finding provided a reliable baseline to evaluate the efficacy of Kakadu Plum Extracts in mitigating ethanol-induced cell death. Subsequently, we employed the 4% ethanol condition to assess the ability of Kakadu Plum Extracts to prevent cell death and reduce reactive oxygen species (ROS) production triggered by ethanol exposure. This approach allowed us to explore the therapeutic potential of Kakadu Plum in counteracting oxidative stress and cellular damage caused by alcohol toxicity.

Kakadu Plum Extracts Confer Robust Protection Against Ethanol-Induced Cytotoxicity in HepG2 Liver Cells

In this study, we evaluated the protective effects of two distinct Kakadu Plum Extracts, KKD-NT and KKD-WA, on ethanol-induced cell death in HepG2 hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Initial toxicity screening revealed that both extracts exhibited minimal cytotoxicity at concentrations up to 200 mg/mL. Based on these findings, subsequent experiments were conducted within a safe concentration range of 20 to 100 mg/mL to ensure cell compatibility while assessing therapeutic potential.

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis confirmed that both extracts are rich in vitamin C (ascorbic acid), a potent antioxidant known to mitigate oxidative stress by neutralising reactive oxygen species (ROS). However, it is important to note that excessive vitamin C levels can paradoxically induce cytotoxicity by generating ROS and disrupting energy homeostasis, particularly in cancerous cells. To investigate the protective efficacy of KKD-NT and KKD-WA against ethanol-induced toxicity, HepG2 cells were co-treated with 4% ethanol and varying concentrations of the extracts (0–100 µg/mL) for 24 hours. Cell viability was then measured using the MTT assay. Ethanol exposure alone reduced cell survival by nearly 50% compared to untreated controls, highlighting its potent cytotoxic effect. Strikingly, co-treatment with Kakadu plum extracts significantly mitigated this effect in a dose-dependent manner.

At the highest concentration tested (100 µg/mL), both KKD-NT and KKD-WA markedly improved cell viability, demonstrating their strong protective properties against ethanol-induced damage. Notably, the KKD-NT extract exhibited superior efficacy in enhancing cell survival compared to KKD-WA, suggesting differential bioactive profiles or mechanisms of protection within the two extracts. These findings underscore the potential of Kakadu plum extracts, particularly Kakadu Plum-Northern Territory, as natural agents capable of defending liver cells from alcohol-induced oxidative stress and cytotoxicity, paving the way for future therapeutic applications in liver health and disease prevention.

Conclusion

This study provides compelling evidence that Kakadu Plum Powders, specifically KKD-NT and KKD-WA, possess exceptionally high levels of ascorbic acid, surpassing those found in commonly available oranges. Our findings highlight the potent protective effects of these extracts against ethanol-induced cytotoxicity in liver-derived HepG2 cells, demonstrating their potential as natural hepatoprotective agents. The Kakadu Plum Extracts exhibited remarkable antioxidant properties, effectively scavenging harmful free radicals generated by alcohol metabolism, thereby mitigating oxidative stress within liver cells. In addition to their antioxidant capacity, both KKD-NT and KKD-WA significantly enhanced the activity of key enzymes involved in alcohol detoxification, alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) and aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH), as confirmed through enzymatic assays. This dual action not only reduces ethanol-induced cellular damage but also promotes efficient alcohol metabolism.

Collectively, these results position Ancient Purity Kakadu Plum Powder as a promising candidate for therapeutic development aimed at preventing and alleviating liver damage caused by alcohol consumption. Their robust antioxidant activity combined with enzyme modulation underscores their potential role in supporting liver health and combating alcohol-related oxidative injury. Future research should explore the clinical applicability of these findings and the molecular mechanisms underlying the protective effects of Kakadu Plum, paving the way for innovative interventions in liver disease management.

”So, I take this word reconciliation and I use it to reconcile people back to Mother Earth, so they can walk this land together and heal one another because she’s the one that gives birth to everything we see around us, everything we need to survive.” – Max Dulumunmun Harrison

References

- Park, J.H.; Kim, Y.; Kim, S.H. Green tea extract (Camellia sinensis) fermented by Lactobacillus fermentum attenuates alcohol-induced liver damage. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2012, 76, 2294–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sudeep, H.; Venkatakrishna, K.; Sundeep, K.; Vasavi, H.; Raj, A.; Chandrappa, S.; Shyamprasad, K. Turcuron: A standardized bisacurone-rich turmeric rhizome extract for the prevention and treatment of hangover and alcohol-induced liver injury in rats. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2020, 16, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobasa, E.M.; Phan, A.D.T.; Manolis, C.; Netzel, M.; Smyth, H.; Cozzolino, D.; Sultanbawa, Y. Effect of sample presentation on the near infrared spectra of wild harvest Kakadu plum fruits (Terminalia ferdinandiana). Infrared Phys. Technol. 2020, 111, 103560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, H.; Sang, S.; Chen, H.; Zuo, X. Temporal trend of gastric cancer burden along with its risk factors in China from 1990 to 2019, and projections until 2030: Comparison with Japan, South Korea, and Mongolia. Biomark. Res. 2021, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Eshak, E.S.; Shirai, K.; Liu, K.; Dong, J.Y.; Iso, H.; Tamakoshi, A.; JACC Study Group. Alcohol Consumption and Risk of Gastric Cancer: The Japan collaborative cohort study. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 31, 30–36. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, K.-W.; Won, Y.-J.; Oh, C.-M.; Kong, H.-J.; Lee, D.H.; Lee, K.H. Cancer statistics in Korea: Incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2014. Cancer Res. Treat. 2017, 49, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchenko, L.; Davydov, B.; Terebilina, N.; Baronets, V.Y.; Zhuravleva, A. Oxidative stress in the alcoholic liver disease. Biochem. (Mosc.) Suppl. Ser. B Biomed. Chem. 2014, 8, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohashi, K.; Pimienta, M.; Seki, E. Alcoholic liver disease: A current molecular and clinical perspective. Liver Res. 2018, 2, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goc, Z.; Kapusta, E.; Formicki, G.; Martiniaková, M.; Omelka, R. Effect of taurine on ethanol-induced oxidative stress in mouse liver and kidney. Chin. J. Physiol. 2019, 62, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.I.; Kim, H.J.; Boo, Y.C. Effect of green tea and (-)-epigallocatechin gallate on ethanol-induced toxicity in HepG2 cells. Phytother. Res. 2008, 22, 669–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, J.; Han, J.; Lee, C.; Yoon, M.; Jung, Y. Pathophysiological Aspects of Alcohol Metabolism in the Liver. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakhari, S. Overview: How is alcohol metabolized by the body? Alcohol Res. Health 2006, 29, 245. [Google Scholar]

- Vairappan, B. Cholesterol Regulation by Leptin in Alcoholic Liver Disease. In Molecular Aspects of Alcohol and Nutrition; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 187–200. [Google Scholar]

- Ghazali, R.; Patel, V.B. Alcohol metabolism: General aspects. In Molecular Aspects of Alcohol and Nutrition; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Sha, K.; Choi, S.-H.; Im, J.; Lee, G.G.; Loeffler, F.; Park, J.H. Regulation of ethanol-related behavior and ethanol metabolism by the Corazonin neurons and Corazonin receptor in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e87062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wu, D.; Cederbaum, A.I. Alcohol, oxidative stress, and free radical damage. Alcohol Res. Health 2003, 27, 277. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Poljsak, B.; Milisav, I. NAD+ as the link between oxidative stress, inflammation, caloric restriction, exercise, DNA repair, longevity, and health span. Rejuvenation Res. 2016, 19, 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lu, Y.; Cederbaum, A.I. CYP2E1 and oxidative liver injury by alcohol. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2008, 44, 723–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- She, X.; Wang, F.; Ma, J.; Chen, X.; Ren, D.; Lu, J. In vitro antioxidant and protective effects of corn peptides on ethanol-induced damage in HepG2 cells. Food Agric. Immunol. 2016, 27, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Butterfield, D.A. Oxidative stress in neurodegenerative disorders. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2006, 8, 1971–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, P.A. Aboriginal People and Their Plants; Rosenberg Publishing: Kenthurst, NSW, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Akter, S.; Netzel, M.E.; Fletcher, M.T.; Tinggi, U.; Sultanbawa, Y. Chemical and nutritional composition of Terminalia ferdinandiana (kakadu plum) kernels: A novel nutrition source. Foods 2018, 7, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gorman, J.T.; Wurm, P.A.; Vemuri, S.; Brady, C.; Sultanbawa, Y. Kakadu Plum (Terminalia ferdinandiana) as a sustainable indigenous agribusiness. Econ. Bot. 2020, 74, 74–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, J. Native Plants of Northern Australia; Reed New Holland: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Phan, A.D.T.; Damyeh, M.S.; Chaliha, M.; Akter, S.; Fyfe, S.; Netzel, M.E.; Cozzolino, D.; Sultanbawa, Y. The effect of maturity and season on health-related bioactive compounds in wild harvested fruit of Terminalia ferdinandiana (Exell). Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 56, 6431–6442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Bajpai, V.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, B.; Srivastava, M.; Rameshkumar, K. Comparative profiling of phenolic compounds from different plant parts of six Terminalia species by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry with chemometric analysis. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 87, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shami, A.-M.M.; Philip, K.; Muniandy, S. Synergy of antibacterial and antioxidant activities from crude extracts and peptides of selected plant mixture. BMC Complementary Altern. Med. 2013, 13, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Williams, D.J.; Edwards, D.; Pun, S.; Chaliha, M.; Burren, B.; Tinggi, U.; Sultanbawa, Y. Organic acids in Kakadu plum (Terminalia ferdinandiana): The good (ellagic), the bad (oxalic) and the uncertain (ascorbic). Food Res. Int. 2016, 89, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sommano, S.; Caffin, N.; Kerven, G. Screening for antioxidant activity, phenolic content, and flavonoids from Australian native food plants. Int. J. Food Prop. 2013, 16, 1394–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tan, A.C.; Konczak, I.; Ramzan, I.; Sze, D.M.-Y. Native Australian fruit polyphenols inhibit cell viability and induce apoptosis in human cancer cell lines. Nutr. Cancer 2011, 63, 444–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirdaarta, J.; Matthews, B.; Cock, I. Kakadu plum fruit extracts inhibit growth of the bacterial triggers of rheumatoid arthritis: Identification of stilbene and tannin components. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 17, 610–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.C.; Konczak, I.; Ramzan, I.; Zabaras, D.; Sze, D.M.-Y. Potential antioxidant, antiinflammatory, and proapoptotic anticancer activities of Kakadu plum and Illawarra plum polyphenolic fractions. Nutr. Cancer 2011, 63, 1074–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, M.H.; Sirdaarta, J.; Matthews, B.; Greene, A.C.; Cock, I.E. Growth Inhibitory Activity of Kakadu Plum Extracts Against the Opportunistic Pathogenclostridium Perfringens: New Leads in the Prevention and Treatment of Clostridial Myonecrosis. Pharmacogn. J. 2016, 8, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sprince, H.; Parker, C.M.; Smith, G.G.; Gonzales, L.J. Protective action of ascorbic acid and sulfur compounds against acetaldehyde toxicity: Implications in alcoholism and smoking. Agents Actions 1975, 5, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, P.; Ray, A.; Jena, S.; Nayak, S.; Mohanty, S. Influence of extraction methods and solvent system on the chemical composition and antioxidant activity of Centella asiatica L. leaves. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2021, 33, 101971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simu, S.Y.; Ahn, S.; Castro-Aceituno, V.; Singh, P.; Mathiyalangan, R.; Jiménez-Pérez, Z.E.; Yang, D. Gold nanoparticles synthesized with fresh panax ginseng leaf extract suppress adipogenesis by downregulating PPAR/CEBP signaling in 3T3-L1 mature adipocytes. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol 2018, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Markus, J.; Mathiyalagan, R.; Kim, Y.-J.; Abbai, R.; Singh, P.; Ahn, S.; Perez, Z.E.J.; Hurh, J.; Yang, D.C. Intracellular synthesis of gold nanoparticles with antioxidant activity by probiotic Lactobacillus kimchicus DCY51T isolated from Korean kimchi. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2016, 95, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalodia, N.R.; Nariya, P.B.; Shukla, V.; Acharya, R. In vitro antioxidant activity of hydro alcoholic extract from the fruit pulp of Cassia fistula Linn. AYU (An Int. Q. J. Res. Ayurveda) 2013, 34, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Castro-Aceituno, V.; Ahn, S.; Simu, S.Y.; Singh, P.; Mathiyalagan, R.; Lee, H.A.; Yang, D.C. Anticancer activity of silver nanoparticles from Panax ginseng fresh leaves in human cancer cells. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2016, 84, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciuclan, L.; Ehnert, S.; Ilkavets, I.; Weng, H.-L.; Gaitantzi, H.; Tsukamoto, H.; Ueberham, E.; Meindl-Beinker, N.M.; Singer, M.V.; Breitkopf, K.; et al. TGF-β enhances alcohol dependent hepatocyte damage via down-regulation of alcohol dehydrogenase I. J. Hepatol. 2010, 52, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.Y.; Cui, Z.G.; Lee, S.R.; Kim, S.J.; Kang, H.K.; Lee, Y.K.; Park, D.B. Effects of Asparagus officinalis extracts on liver cell toxicity and ethanol metabolism. J. Food Sci. 2009, 74, H204–H208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bobasa, E.M.; Phan, A.D.T.; Netzel, M.E.; Cozzolino, D.; Sultanbawa, Y. Hydrolysable tannins in Terminalia ferdinandiana Exell fruit powder and comparison of their functional properties from different solvent extracts. Food Chem. 2021, 358, 129833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzolino, D.; Phan, A.D.T.; Netzel, M.E.; Smyth, H.; Sultanbawa, Y. The use of vibrational spectroscopy to predict vitamin C in Kakadu plum powders (Terminalia ferdinandiana Exell, Combretaceae). J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 3208–3213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cozzolino, D.; Phan, A.D.T.; Aker, S.; Smyth, H.E.; Sultanbawa, Y. Can Infrared Spectroscopy Detect Adulteration of Kakadu Plum (Terminalia ferdinandiana) Dry Powder with Synthetic Ascorbic Acid? Food Anal. Methods 2021, 14, 1936–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtney, R.; Sirdaarta, J.; Matthews, B.; Cock, I. Tannin components and inhibitory activity of Kakadu plum leaf extracts against microbial triggers of autoimmune inflammatory diseases. Pharmacogn. J. 2015, 7, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Phan, A.D.T.; Adiamo, O.; Akter, S.; Netzel, M.E.; Cozzolino, D.; Sultanbawa, Y. Effects of drying methods and maltodextrin on vitamin C and quality of Terminalia ferdinandiana fruit powder, an emerging Australian functional food ingredient. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 5132–5141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, R.; Bowyer, M.; Vuong, Q. Australian native fruits: Potential uses as functional food ingredients. J. Funct. Foods 2019, 62, 103547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaurinovic, B.; Vastag, D. Flavonoids and Phenolic Acids as Potential Natural Antioxidants; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Netzel, M.; Netzel, G.; Tian, Q.; Schwartz, S.; Konczak, I. Native Australian fruits—a novel source of antioxidants for food. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2007, 8, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warinhomhoun, S.; Muangnoi, C.; Buranasudja, V.; Mekboonsonglarp, W.; Rojsitthisak, P.; Likhitwitayawuid, K.; Sritularak, B. Antioxidant Activities and Protective Effects of Dendropachol, a New Bisbibenzyl Compound from Dendrobium pachyglossum, on Hydrogen Peroxide-Induced Oxidative Stress in HaCaT Keratinocytes. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jadid, N.; Hidayati, D.; Hartanti, S.R.; Arraniry, B.A.; Rachman, R.Y.; Wikanta, W. Antioxidant activities of different solvent extracts of Piper retrofractum Vahl. using DPPH assay. In AIP Conference Proceedings, Proceeding of the International Biology Conference 2016: Biodiversity and Biotechnology for Human Welfare, Surabaya, Indonesia, 15 October 2016; Murkovic, M., Risuleo, G., Eds.; AIP Publishing LLC: Melville, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Farshori, N.N.; Al-Sheddi, E.S.; Al-Oqail, M.M.; Hassan, W.H.; Al-Khedhairy, A.A.; Musarrat, J.; Siddiqui, M.A. Hepatoprotective potential of Lavandula coronopifolia extracts against ethanol induced oxidative stress-mediated cytotoxicity in HepG2 cells. Toxicol. Ind. Health 2015, 31, 727–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.-J.; Byun, J.-S.; Kwon, H.S.; Kim, D.-Y. Cellular toxicity driven by high-dose vitamin C on normal and cancer stem cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 497, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.S.; Chu, F.-H.; Hsieh, H.-W.; Liao, J.-W.; Li, W.-H.; Lin, J.C.-C.; Shaw, J.-F.; Wang, S.-Y. Antroquinonol from ethanolic extract of mycelium of Antrodia cinnamomea protects hepatic cells from ethanol-induced oxidative stress through Nrf-2 activation. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 136, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaliha, M.; Sultanbawa, Y. Terminalia ferdinandiana, a traditional medicinal plant of Australia, alleviates hydrogen peroxide induced oxidative stress and inflammation, in vitro. J. Complementary Integr. Med. 2020, 17, 20190008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, J.M.; Park, J.C. Effects of the aerial parts of Orostachys japonicus and its bioactive component on hepatic alcohol-metabolizing enzyme system. J. Med. Food 2006, 9, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]